26

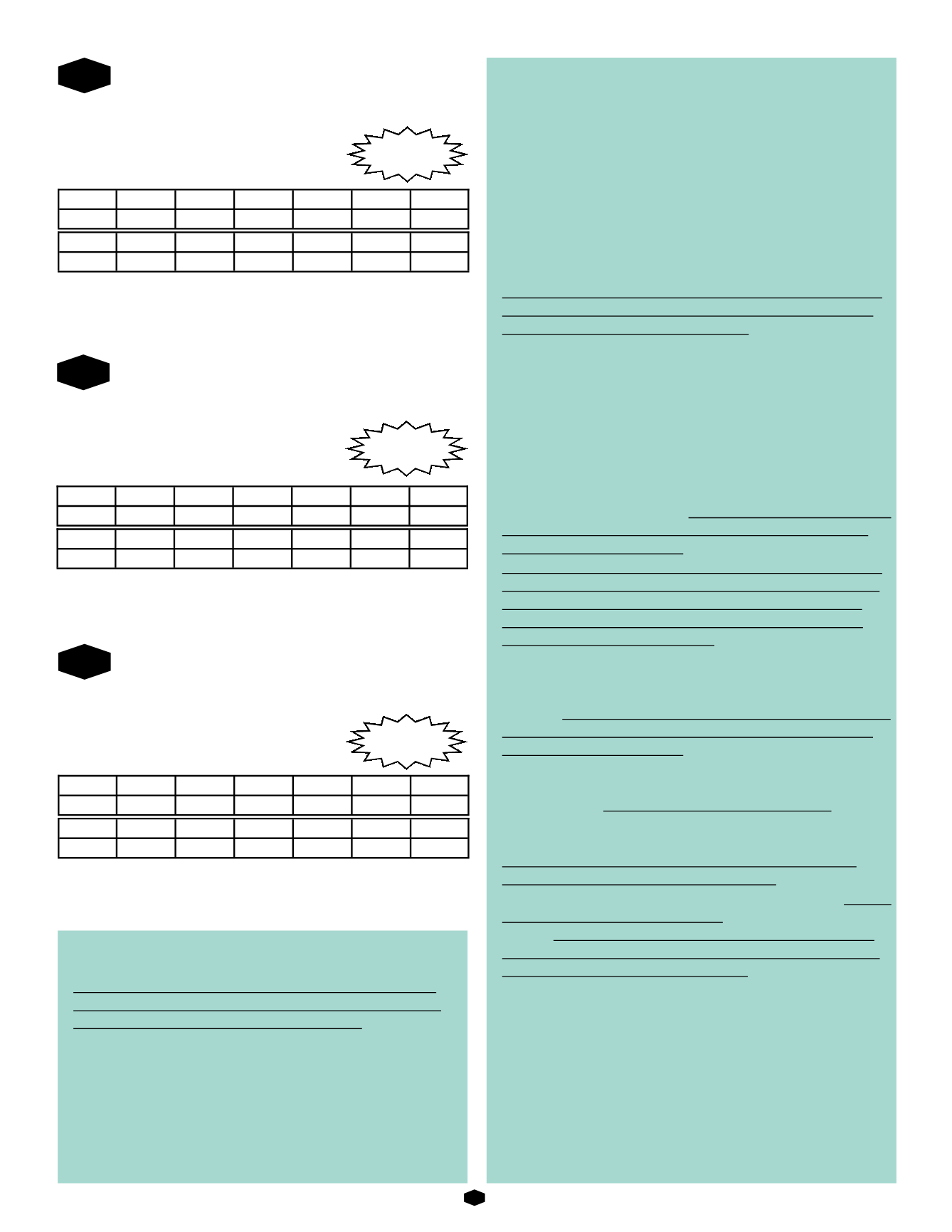

BARRETT 5267 110 DA

Calved: 8/22/15

Reg#: 18502555

Tattoo: 5267

Sitz Upward 307R

Actual Scrotal: 38.5 cm

Sitz Dash 10277

Sitz Everelda Entense 2665

SAV Net Worth 4200

Barrett Rita 110 of 1709 NW

Barretts 1709 of 1204 5522

Lots of powerhouse cattle behind this bull! Generations deep of cattle select-

ed for 50+ years of growth, power, maternal. This bull should leave excellent

daughters. Dash only adds to the quality females this bull should sire.

110

CED

BW

WW

YW

SC

CEM

Milk

+9

+.2

+50

+85

+.54

+12

+21

CW

Marb

RE

Fat

$EN

$W

$B

+26

+.53

+.61

+.053

+12.13

+58.88

+96.46

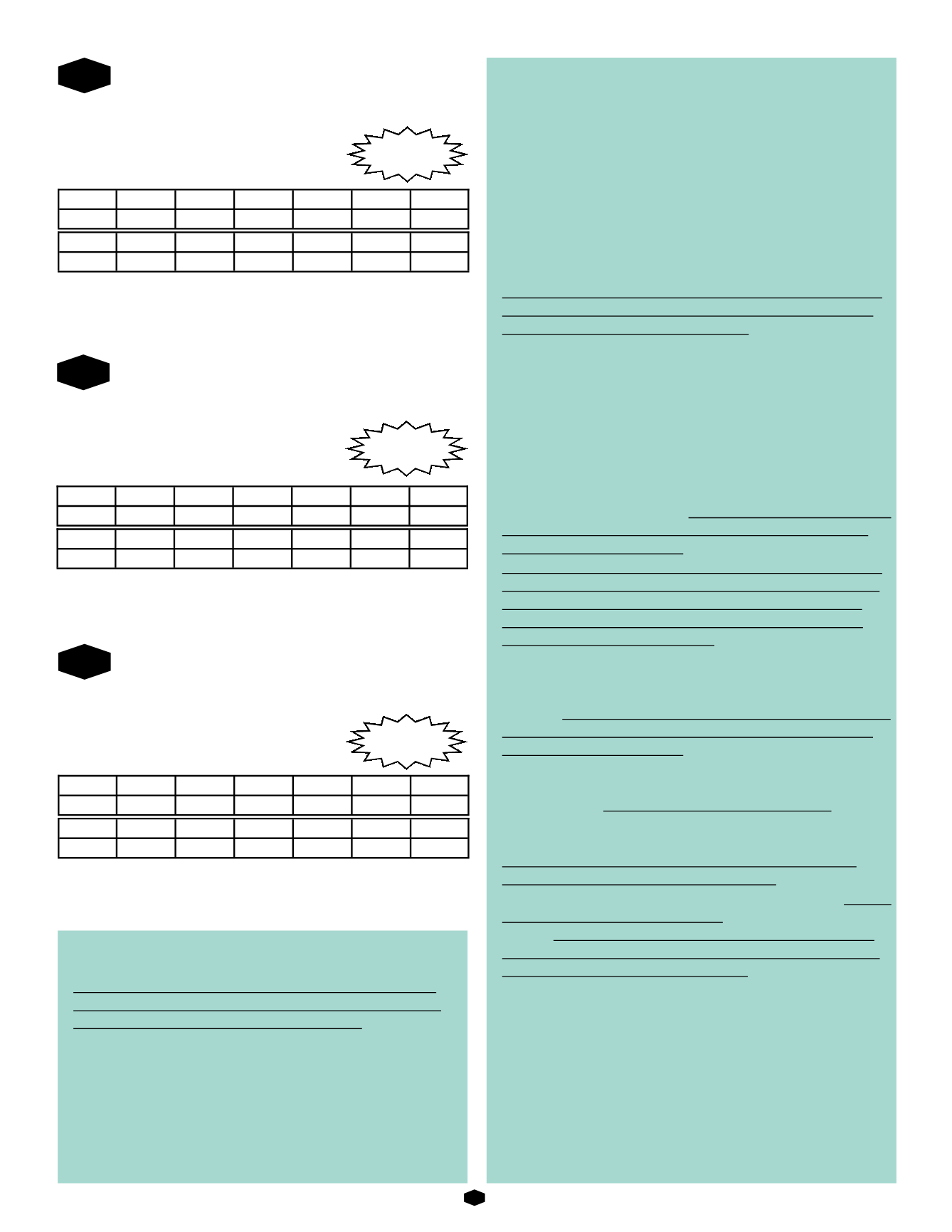

BARRETT 5268 118 DA

Calved: 9/16/15

Reg#: 18502556

Tattoo: 5268

Sitz Upward 307R

Actual Scrotal: 36.5 cm

Sitz Dash 10277

Sitz Everelda Entense 2665

SAV Net Worth 4200

Barrett Rita 118 of 1709 NW

Barretts 1709 of 1204 5522

111

CED

BW

WW

YW

SC

CEM

Milk

+13

+.1

+38

+72

+1.56

+14

+21

CW

Marb

RE

Fat

$EN

$W

$B

+27

+.65

+.45

+.058

+9.39

+37.48

+96.69

Potential

Heifer Bull on

Larger Heifers

Potential

Heifer Bull on

Larger Heifers

How to control costs & spur cowherd revenues,

Wes Ishmael, reprinted with permission, BEEF Magazine

“Controlling cost in the cow-calf sector is more important

than creating revenue,” said David Lalman, Extension beef

cattle specialist at Oklahoma State University.

In part, Lalman explained to those attending this summer’s

annual meeting of the Beef Improvement Federation (BIF),

the reason is that the cost of adding a pound of weaning

weight is about the same as its value over time.

For instance, the cost per hundredweight of calf produced in

Texas, Oklahoma and New Mexico increased an average of

$5 per year from 1991 to 2015, according to data from the

Southwest Cow-Calf Standardized Performance Analysis (SW-

High $EN, high heifer pregnancy, low mature weight—easy-maintaining fe-

males expected. Extremes are easy to brag about—but breeders need to look

at the whole picture. Dash semen is limited because he has been used a lot.

I wonder why?

SPA). Calf prices increased an average of $5.25 per year.

Likewise, data from the Kansas Farm Management Associa-

tion (KFMA) at Kansas State University (K-State) show the

cost per pound of additional weaning weight from 2010 to

2014 was about .96 (basis 90% weaning rate), while the value

was about .86 (basis Oklahoma City mean average).

“On average, the cost associated with increasing weaning

weight in the Kansas data was slightly greater than the value

of increased weaning weight,” Lalman explained. “The rela-

tive value of additional weaning weight is highly variable over

time, and therefore, the profitability of managing to achieve

greater weaning weight will be highly variable over time.

Clearly, in the context of an enterprise that sells at weaning,

there is more low-hanging fruit in cutting or managing cost

than there is in increasing production.”

Lalman and other researchers at OSU and K-State also looked

at cow-calf benchmarking data — too scarce in the industry

— from the Cow Herd Appraisal Performance System

(CHAPS) program at North Dakota State University; and

FINBIN, data from the Center for Farm Financial Manage-

ment at the University of Minnesota.

The breakeven nature of weaning weight over the long haul

may offer a plausible explanation for the fact that weaning

performance — measured by such databases — remains

mostly static across decades, despite the fact that the genetic

trend for growth in the heaviest-used breeds continues to

increase at a significant rate.

“It may be that genetic potential for production of the seed-

stock sector has simply advanced beyond what the environ-

ment or resources will allow in these regions,” suggested

Clay Mathis, director of the King Ranch Institute of Ranch

Management, at the BIF meeting.

“It is possible that the SPA summaries from the Southwest

and Northern Plains simply show optimization, and that re-

sources are dictating an upper limit to cost-effective perfor-

mance … There is opportunity to improve pregnancy rate and

weaning rate, but the marginal cost of higher performance

may be prohibitive,” he said.

Although calf prices increased 88% between the two eight-

year periods of 1988 to 1995 and 2008 to 2015, when adjust-

ed for inflation, Mathis pointed out prices rose 18%.

At the same time, inflation-adjusted costs — especially those

that matter most to ranch profitability — continue higher.

For instance, the inflation-adjusted cost of labor was 9%

higher, and the cost of feed was 24% more.

“Half of the expenses for a cow-calf enterprise can be catego-

rized as depreciation, labor or feed,” Mathis said. “Other ex-

penses, like repairs and maintenance, fertilizer, fuel, leases

and veterinary services are important when taken together,

but independently are less important.”

In the most recent KFMA data, Lalman explained 67.8% of

the profitability differences between the top third and

bottom third of producers was due to lower cost of produc-

tion of the highest-profit producers.

“Future efficiencies and profits will not be mutually exclusive

efforts to controlling costs and increasing revenues,” Mathis

said. “Success will come from optimizing expenses and per-

formance by building a production system that will yield the

lowest unit cost of production for the most valuable calf that

can be produced in the operational environment.”

BARRETT 5272 253 DA

Calved: 9/12/15

Reg#: 18502558

Tattoo: 5272

Sitz Upward 307R

Actual Scrotal: 34 cm

Sitz Dash 10277

Sitz Everelda Entense 2665

SAV Net Worth 4200

Barrett Pride 253 1406 NW

Barretts Pride 1406 210 423

Dash is one of the highest $W bulls in the breed with his kind of accuracy.

Low accuracy bulls change with time generally. That’s why we like to wait—

slower? Maybe… but actually faster in the long run!

109

CED

BW

WW

YW

SC

CEM

Milk

+6

+2.2

+51

+92

+.73

+10

+24

CW

Marb

RE

Fat

$EN

$W

$B

+26

+.69

+.43

+.051

-.70

+50.11

+98.96

Potential

Heifer Bull on

Larger Heifers